Introduction

Entropy is the lifeblood of cryptography. If your cryptographic system’s randomness is weak, you’ve already lost - no matter how mathematically secure the algorithm is.

As part of this year’s Def Con 33 - Quantum Village CTF, the point was driven home in a challenge involving post-quantum cryptography and low-entropy randomness. While we ended up working with a NIST selected Post-Quantum signature scheme, this challenge showed that being quantum-safe doesn’t mean being low-entropy safe. As an industry we should be keeping the migration to PQC in mind, operationally we also need to ensure that we are implementing it securely to avoid potential vulnerabilities like what we see in this challenge.

Challenge Introduction

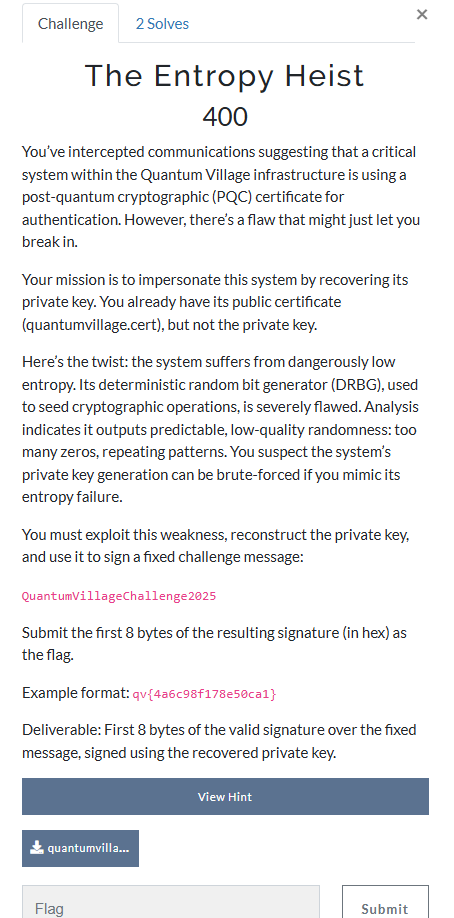

We start off this challenge with a descriptive narrative and a certificate file.

Alright we’re given a certificate so let’s take a look and see if we can extract any additional information.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

openssl x509 -in quantumvillage.cert -inform PEM -text -noout

...

Public Key Algorithm: 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.18

Unable to load Public Key

80EB0B7BAF7F0000:error:03000072:digital envelope routines:X509_PUBKEY_get0:decode error:../crypto/x509/x_pubkey.c:458:

80EB0B7BAF7F0000:error:03000072:digital envelope routines:X509_PUBKEY_get0:decode error:../crypto/x509/x_pubkey.c:458:

...

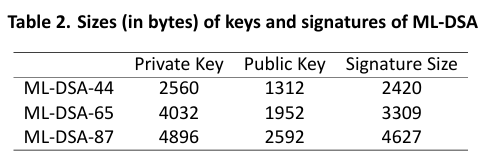

A quick search of the OID reveals that this is indeed a post-quantum signature scheme, specifically ML-DSA-65, a variant of the Dilithium algorithm.

In order to move to supporting the NIST standardized OIDs for Post-Quantum algorithms, the following algorithms have switched their underlying OIDs: ML-DSA-44 now uses 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.17, ML-DSA-65 now uses 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.18, ML-DSA-87 now uses 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.19.

What was interesting is that I was running into public key loading issues.

1

2

$> openssl version

OpenSSL 3.0.2 15 Mar 2022 (Library: OpenSSL 3.0.2 15 Mar 2022)

Which seemed to stem from https://github.com/openssl/openssl/issues/18039. Thankfully, this wasn’t too much of a blocker, but did require a custom route to dump the public key.

We already know by the OID that we are working with ML-DSA-65. There are a few ways you could get the public key from the cert file, even just carving out the cert file at certain byte offsets, but I ended up creating a small utility script, that also checks for the various key lengths to determine which variant of ML-DSA we are working with, and extracts the public key to it’s own separate file. This is a bit of foreshadowing for later parts.

Running the utility script confirms our previous details, and also writes out pk.bin and sig.bin.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

python .\dump.py .\quantumvillage.cert

SubjectPublicKeyInfo.algorithm OID: 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.18

SignatureAlgorithm OID: 2.16.840.1.101.3.4.3.18

Public key length (pk.bin): 1952 bytes (raw key payload)

Certificate signature length: 3309 bytes

Wrote pk.bin and sig.bin

Size hints:

- Dilithium3: pk=1952, sig=3309 (matches: 2/2)

Great, I know it’s ML-DSA-65, and I have the public key. Now what? Let’s look at how ML-DSA-65 uses RNG and how we can exploit weak entropy.

Background on ML-DSA

Key Pair Generation

Before we talk about forging signatures, it’s worth stepping back to look at how ML-DSA-65 actually produces its public/private key pairs. The overall FIPS204 documentation is a handy reference here. Looking through it we can see the key generation process is deterministic once you fix a seed.

When you call OQS_SIG_keypair (specifically for the OQS library, used in this challenge), the algorithm first asks the system’s random number generator for a block of entropy. For ML-DSA-65 this seed is 256 bit. In a healthy system, these bits should be unpredictable, drawn from a cryptographically secure RNG. But we know this isn’t quite the case!

Its deterministic random bit generator (DRBG), used to seed cryptographic operations is severely flawed. Analysis indicates it outputs predictable, low-quality randomness: too many zeros, repeating patterns.

Deterministic vs. Hedged Signing

According to NIST FIPS 204, ML-DSA supports two signing approaches:

Deterministic signing The randomness is derived only from the message and private key. This guarantees the same message always produces the same signature. Deterministic mode doesn’t depend on an RNG, but it’s more vulnerable to side-channel or fault attacks because the process is entirely predictable.

Hedged signing (the default) A blend of two randomness sources is used:

- A fresh 256-bit (32 bytes) random value pulled from the RNG at signing time.

- Pseudorandomness derived from the message and key.

The “hedge” is meant to protect against two classes of failure. First, if the RNG is broken, the message/key pseudorandomness still keeps the commitment value secure. Secondly, if the deterministic path leaks side-channel info, the fresh randomness adds noise and makes exploitation harder… IF the RNG is not also broken.

Based on what we know about the challenge, you might think we are dealing with deterministic signing (since we need to sign, deterministically, the challenge string to get the flag), but ultimately the indications towards the weak entropy was the hint towards hedged signing.

Setting Up - OQS

Alright, enough theory, let’s get to work. The plan is essentially a few steps:

- Compile the OpenQuantumSafe library locally

- Control the random number generator (RNG)

- Iterate through key pair generation with our various RNG attempts

- If our generated public key matches the public key we extracted from the certificate, we have the private key!

So first, we need to compile the OpenQuantumSafe library. I cloned over https://github.com/open-quantum-safe/liboqs and compiled it. Funny enough, I ran out of memory on the device I was working from so had to tweak a few of the settings and turn off portions I didn’t need for the compile to work.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

cmake -S liboqs -B liboqs/build \

-DOQS_BUILD_ONLY_LIB=ON \

-DOQS_ENABLE_KEM=OFF \

-DOQS_ENABLE_SIG=ON \

-DOQS_ENABLE_SIG_ML_DSA=ON \

-DOQS_ENABLE_SIG_FALCON=OFF \

-DOQS_ENABLE_SIG_SPHINCS=OFF \

-DOQS_DIST_BUILD=OFF \

-DOQS_USE_OPENSSL=OFF \

-DOQS_OPT_TARGET=generic \

-DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release

cmake --build liboqs/build --config Release -- -j1

Successfully compiled locally, let’s get the brute force script going.

Et tu, Brute?

I’ll link to the full script at the end of the post, but for now here’s a logical breakdown of what it’s doing.

Setup the ML-DSA-65 structure, including our controlled custom rng

1

2

3

4

5

6

OQS_SIG *sig = OQS_SIG_new("ML-DSA-65");

...

pk = (uint8_t *)malloc(sig->length_public_key);

sk = (uint8_t *)malloc(sig->length_secret_key);

...

OQS_randombytes_custom_algorithm(custom_randombytes);

Where custom_randombytes is a function that provides our low-entropy repeating pattern.

1

2

3

4

5

6

static void custom_randombytes(uint8_t *out, size_t out_len) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < out_len; i++) {

out[i] = seedbuf[seedidx % SEEDSPAN_MAX];

seedidx++;

}

}

Control the RNG during key generation.

While I had setup my brute force script for the long haul, it ended up hitting the right keypair on literally the first try. This has me raise an eyebrow at whether I broke something, but my thought was to iterate in increasing complexity. Starting with fixed bytes, and then expanding into larger, more complex patterns.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

uint8_t seed[SEEDSPAN_MAX];

memset(seed, 0x00, sizeof(seed));

// Quick pass 0: constant-byte seeds (all bytes == v)

{

for (int v = 0; v < 256; v++) {

memset(seed, (uint8_t)v, N);

if (try_seed_and_check(sig, target_pk, target_len, seed, N, found_sk)) {

printf("FOUND (constant-byte): v=%d\n", v);

printf("Seed: ");

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; i++) printf("%02x", seed[i]);

printf("\n");

goto SIGN_OUT;

}

}

fprintf(stderr, "Constant-byte pass: no match.\n");

}

Generate deterministic key pairs and compare to our public key

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

static inline int try_seed_and_check(OQS_SIG *sig,

const uint8_t *target_pk, size_t target_pk_len,

const uint8_t *seed, size_t seed_len,

uint8_t *out_sk) {

// Load seed into seedbuf and reset index

memset(seedbuf, 0x00, SEEDSPAN_MAX);

if (seed_len > SEEDSPAN_MAX) seed_len = SEEDSPAN_MAX;

memcpy(seedbuf, seed, seed_len);

seedidx = 0;

if (OQS_SIG_keypair(sig, pk, sk) != OQS_SUCCESS) return 0;

// Compare generated public key with target public key

if (memcmp(pk, target_pk, target_pk_len) == 0) {

memcpy(out_sk, sk, sig->length_secret_key);

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

Hacker Voice: I'm In

For fun, I included the challenge string in the script directly. Figured if I got lucky and generated the private key, I should be able to sign the message immediately and submit the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

const char *msg = "QuantumVillageChallenge2025";

size_t mlen = strlen(msg);

size_t siglen = sig->length_signature;

uint8_t *signature = (uint8_t *)malloc(siglen);

if (!signature) {

fprintf(stderr, "alloc signature failed\n");

OQS_SIG_free(sig); free(target_pk); free(pk); free(sk); free(found_sk);

return 1;

}

if (OQS_SIG_sign(sig, signature, &siglen, (const uint8_t *)msg, mlen, found_sk) != OQS_SUCCESS) {

fprintf(stderr, "sign failed\n");

OQS_SIG_free(sig); free(target_pk); free(pk); free(sk); free(found_sk); free(signature);

return 1;

}

Last part was compiling the script and kicking it off.

1

cc -O3 -march=native -std=c11 -I ./liboqs/build/include ml_dsa_bruteforce.c ./liboqs/build/lib/liboqs.a -o brute

1

2

3

4

5

./brute

Keygen consumed_first bytes: 32

FOUND (constant-byte): v=1

Signature length: 3309

Flag (first 8 bytes): 86e5a26ca58d642a

Wait, what? I got it almost instantly. I tried submitting the hash…and it wasn’t correct. Ok, that’s more like the CTFs I’m used to. It took me entire too long to figure out what the issue was, so let’s step through a few things I did.

The Private-Private Key?

The first was to confirm I did actually get the right private key. I wrote up another utility script that signed the message with the private key generated, and would verify using the extracted public key. At the very least we can confirm that we have the right key pair.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

./confirm

Keygen consumed_first bytes: 32

Public key match: OK

Signing literal string: "QuantumVillageChallenge2025" (len=27)

Signature length: 3309

Verification: OK

Signature first 8 bytes (hex): 86e5a26ca58d642a

Alright, at least we have “Verification: OK”.

More Non-Entropy!

The second error I figured out was my fixed RNG. I was hardcoding the seed, but I originally was only setting the first 32 bytes (what was needed for the key pair generation).

1

#define SEEDSPAN_MAX 32

At key generation time, ML-DSA-65 only depends on the first 32 bytes of entropy. That’s why constant [0x01] seeds reproduced the private key no matter what came after.

But signing in hedged mode is different. It may consume additional RNG bytes beyond that first block, because it needs “fresh randomness” for the rnd value. If those bytes aren’t controlled, the commitment value will differ, and so will the signature.

In the brute script, that meant that [0x01 × 32] + zeroes gave the right key, but the wrong signature (to what the challenge string was expecting). Only [0x01 × 256] (constant all the way through) aligned perfectly with the challenge’s expected output.

1

2

#define SEEDSPAN_MAX 256

static uint8_t seedbuf[SEEDSPAN_MAX];

Once More Into the Fray

The last issue I encountered was on printing out the signature hash. At this point I knew I had the right private key, and I learned more about the signature process in terms of our RNG values. I still wasn’t able to reproduce the exact signature hash that the challenge expected.

I modified my brute script to also print out the full seed so I could confirm what exactly what being put into the RNG.

1

2

3

4

5

6

./brute

Keygen consumed_first bytes: 32

FOUND (constant-byte): v=1

Seed: 01010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101

Signature length: 3309

Flag (first 8 bytes): 86e5a26ca58d642a

Ok, that’s not the hash though… what else is going on.

When my raw signature bytes didn’t match the flag, the first suspicion was maybe the library was doing something strange with the output.

So I dug into how liboqs actually handles signing. The OQS_SIG_sign function doesn’t do any formatting at all, it simply writes raw bytes into a buffer that you pass in. No casting, no endian juggling. OQS_SIG_sign writes raw bytes into a buffer you provide doc.

I was originally printing the output as:

1

2

3

uint8_t *signature = (uint8_t *)malloc(siglen);

...

for (size_t i = 0; i < 8; i++) printf("%02x", signature[i]);

Which should match the raw output formatting. That eliminated liboqs as the culprit. Ultimately I reached out to the Quantum Village admins and they confirmed I had the right seed, private key, and generally the right answer. What we found out was that my endianness was wrong! There was a 16-bit word endianness swap: each adjacent two-byte pair was reversed, while the overall byte order was preserved.

What I think happened was that the challenge flag was originally printed out in a slightly different format. Something like the following:

1

2

uint16_t *p = (uint16_t *)signature;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) printf("%04x", p[i]);

I may be completely off base and missed something here, so would love to hear if someone else has insights.

But with understanding that the endianness was incorrect, that was a small tweak to the print statement in my script. Modifying it to:

1

2

3

4

printf("Flag (first 8 bytes, pair-swapped): ");

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i += 2) {

printf("%02x%02x", signature[i+1], signature[i]); // swap adjacent bytes

}

At which point, the brute script generated:

1

2

3

4

5

6

./brute

Keygen consumed_first bytes: 32

FOUND (constant-byte): v=1

Seed: 01010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101

Signature length: 3309

Flag (first 8 bytes, pair-swapped): e5866ca28da52a64

And, tada, the flag qv{e5866ca28da52a64} was correct! Good enough to get first blood as well!

Summary

This challenge was a perfect reminder that cryptography is more than math on paper. ML-DSA-65, like other lattice-based signature schemes, is designed to withstand quantum adversaries. In practice however, security hinges on details: how randomness is seeded and how entropy sources behave.

A constant-byte RNG seed turned “hedged” signing into deterministic signing. This isn’t a weaknesses in ML-DSA itself, it is an artifact of implementation, environment, and representation. And in the real world, attackers don’t care whether a failure is in the math or in implementation; oftentimes it is easier to exploit improper implementation.

As quantum-safe algorithms move from research into production systems, these lessons matter. The math gives us the foundation, but operational implementation keeps the structure secure.

Finally, a big thank you to the Quantum Village team and the CTF organizers. Challenges like The Entropy Heist don’t just test skills, they teach nuance, highlight blind spots, and prepare us for the future of cryptography in a post-quantum world.

The full scripts to what I covered above can be found at https://github.com/padraignix/quantum-challenges.

Thanks folks, until next time!