Introduction

As mentioned in my first post of the series on Shor’s Algorithm in Action, the next step is to understand what can be done to ensure the future of our underlying security and privacy processes are quantum-safe. In this post we will go over a few of the proposals brought forward, quickly touching some of the fundamental math behind them. Additionally, we will cover the state of the NIST’s quantum-safe standardization efforts. At the time of this writing several candidates have been selected for standardization while more are undergoing evaluation in the current round.

This second post will help lay the groundwork for the next post, where we will take what we have learned and explore experimental quantum-safe utilities and open-source software. The goal is not necessarily to provide an end-to-end roadmap, as some aspects are still unknown today, however understanding the goal of what we are trying to achieve (quantum-safe cryptography) and having the basics of the current threats and PQC proposals allows us to critically evaluate what is coming out and be ready to implement and/or pivot as the landscape evolves. Going back to a childhood quote - “knowing is half the battle”.

Why Do We Need This?

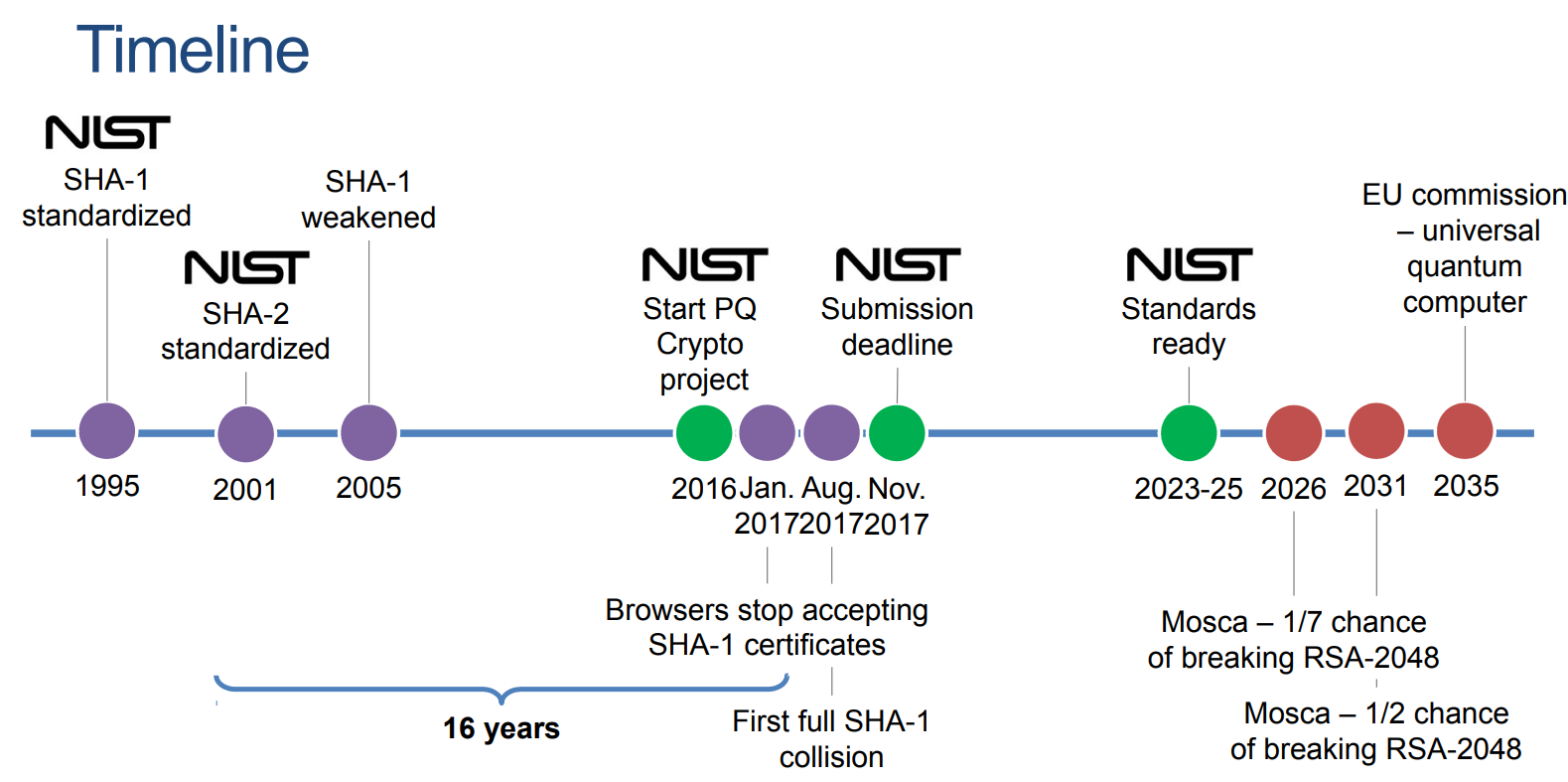

Mentions of “must start now” or “we are already too late” pop up in news and interviews quite often, but why is that exactly? We saw in the previous post how Shor’s provides a proven way to factor prime numbers, sure, but aren’t we at the engineering problem portion, where it may take many years before a quantum computer can practically break the key sizes in use today? Technically you would be correct. But there are a few additional aspects that we need to keep in mind.

Firstly, the “years away” comment is with our current understanding. This nascent field is very much evolving at a growing pace. Recently an arxiv publication An Efficient Quantum Factoring Algorithm has claimed to find a way to reduce the number of quantum gates from 4 million to 100k, at a trade-off of requiring more qubits. This approach has not proved physically implementable yet, but serves to illustrate just how fast the field can and is changing.

Secondly, we need to think of the full lifecycle of the data we are trying to protect. Just because it is secure, at the moment, does that mean we can ignore the state of that particular data 1, 5, 10 years down the road? In what many call “hack now, decrypt later” we need to essentially assume that our data is already compromised, in its encrypted form, and be sure that it cannot be decrypted for the useful lifetime of that data. A recent example of this classically happened with the Lastpass Breach. This is a classical example since, to my knowledge at least, there is no practical quantum computer being leveraged to break encryption today, however when one will become available, data harvested even now may be subject to breach years from now.

The sooner the shift to quantum-safe cryptography is done from an industry perspective, the quicker these future threats can be addressed.

Let’s jump into some of those approaches and understand how this can be done.

NIST Standardization

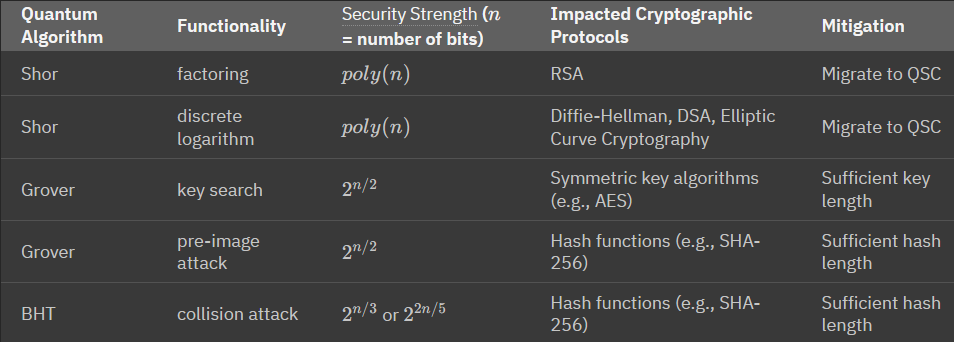

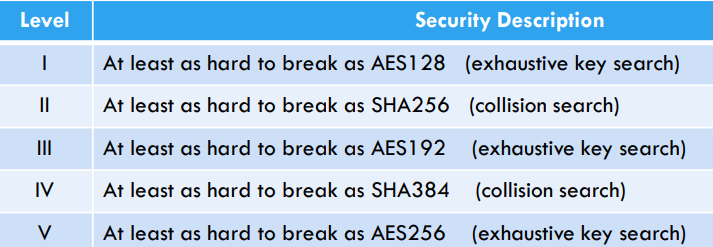

Understanding that a new set of quantum-safe standards would be required in the industry, the NIST organization kicked off its Post-Quantum Cryptography efforts with a call for proposals from the community. These proposals fit into varying categories defined by NIST:

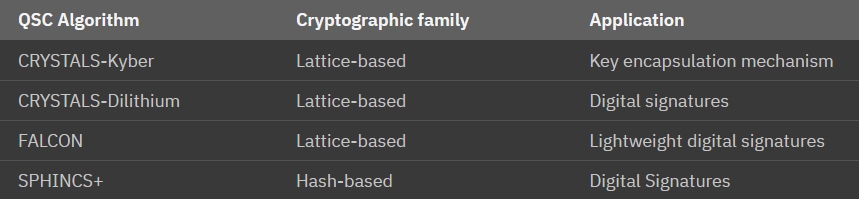

Over the years, through several rounds of proposals, feedback, and community scrutiny, the first set of algorithms were chosen for standardization. (source for below).

With the third round and initial selections identified, a fourth round is underway to identify additional approaches to diversify the current selections. While the fourth round is progressing, NIST has already released three FIPS drafts for the already selected algorithms.

High-Level Math

Let’s take a look at the currently selected algorithms from NIST. Both from a applicability perspective, but for the purposes of this section more for the underlying cryptographic families

Alright, I think it’s safe to say we should look at Lattice-based. Additionally, the recent online IBM course Practical introduction to quantum-safe cryptography does cover this in more mathematical and practical details and I do suggest taking a look for anyone interested.

Lattice-Based Cryptography

First thing’s first - what is a lattice? Lattices are mathematical structures that can be thought of as a grid of regularly spaced points in n-dimensional space. These points are arranged in such a way that they form a repeating pattern. In the context of lattice-based cryptography, lattices are used to create hard mathematical problems that are believed to be resistant to attacks, including those by quantum computers, making them an area of interest for PQC.

A few of the ways lattices are used:

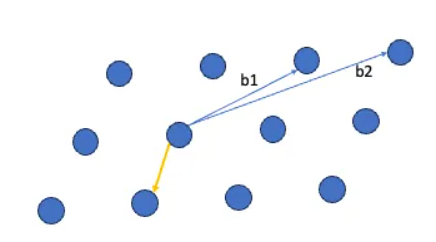

- Shortest Vector Problem (SVP): SVP is a fundamental problem in lattice-based cryptography. It asks for the shortest non-zero vector within a lattice. Finding this shortest vector is a computationally hard problem and forms the foundation for many lattice-based cryptographic schemes.

- Closest Vector Problem (CVP): CVP is another fundamental problem in lattice-based cryptography. It seeks to find the lattice point closest to a given target point. This problem is also computationally challenging.

Bounded Distance Decoding (BDD): BDD is a problem that involves finding a lattice point whose distance from a given target point is below a certain threshold.

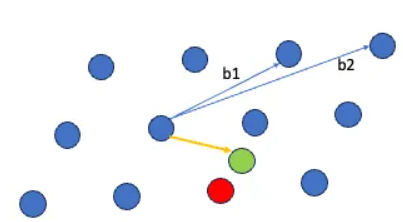

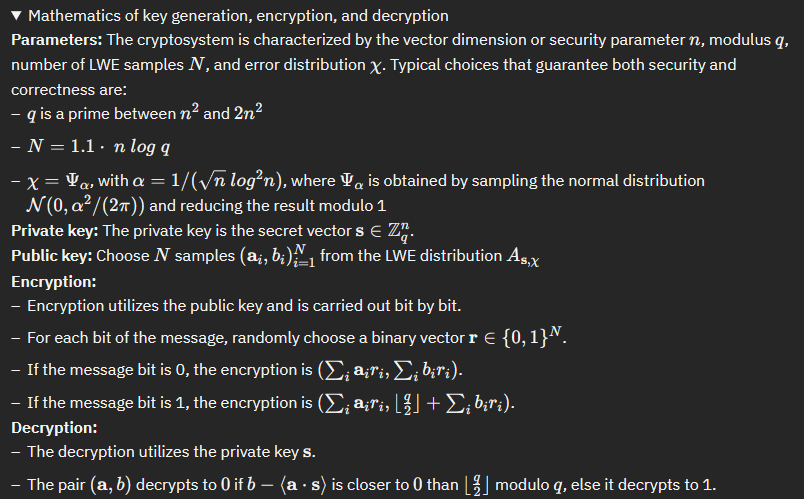

Learning With Errors (LWE): LWE is a specific problem in lattice-based cryptography where errors (noise) are introduced into the lattice points. It is hard to distinguish between lattice points with errors and those without. LWE is a foundational problem for encryption and key exchange in lattice-based cryptography.

Ring-LWE: A variant of LWE, Ring-LWE operates with polynomial rings instead of integers. This variant offers certain computational efficiency advantages at a potential security trade-off.

Module-LWE is a variant of the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem. In Module-LWE, the lattice vectors are taken modulo a fixed module, which is an integer or a polynomial ring. This modification to the traditional LWE problem introduces a unique set of challenges and applications.

The Practical introduction to quantum-safe cryptography - LWE in Python has a specific section where you can step through a practical implementation of LWE in Python. Instead of repasting my run-through here I highly suggest you read the mathematical definition and then reinforce it by stepping through the practical exercise.

Summary

So far we’ve looked at first the potential threat quantum computing brings to our current security implementations, and now the current approaches being taken to develop a standardized “quantum-safe” approach. Additionally, we’ve started going down the rabbit hole of exploring the underlying mathematic concepts of some of the NIST-selected approaches and alluded to a hands-on approach to explore that math.

In the next part of the series we will bring it all together and look at some experimental branches of utilities and tools we use on a day-to-day basis. Specifically, I’ll work on re-implementing libraries from Open Quantum Safe and taking a look at how we adjust configurations for SSH and others to establish quantum-safe communications with my test lab. Here’s to the practical implementation!

Thanks folks, until next time!