Introduction

After last year’s event success and the sheer amount of Quantum computing and Quantum Machine Learning that was learned I was looking forward coming back to the coding challenges in 2022. Focusing on Xanadu’s Pennylane offering, this year was broken down into 5 categories: Pennylane101, Algorithms, Games, Chemistry, QML, each with 5 challenges increasing in difficulty. Overall the look and feel was similar from 2021, down to the submission portal and “Jury” clarification system to send questions to the team running the event.

I feel the difficulty of the challenges was mostly appropriate. Not coming from any official Quantum Computing background (you can pretty much see most of my self-education through the various posts I’ve made here) I was happy to say that there were a few challenges where I read the description and could almost immediately pinpoint the approach we would need to leverage - partial spoiler to Games 400/500 below. There were a few frustrating points as with any event I’ve participated in, and I’ll list those out in more detail near the end.

I wanted to take a different approach to writing up this event. I’ll be sharing my solutions on github, however I wanted to highlight a few of the challenges I really enjoyed. Instead of focusing on any specific track, like last year’s post-event, I’ll this year I’ll be covering challenges that either covered a specific quantum computing concept in practice, or challenges that expanded something otherwise trivial, that I wouldn’t have thought of implementing prior to Qhack. These types of practical implementation takeaways are where events like QHack shine; combine a hands-on approach, with a gamified learning angle, and you end up not only with learning specific implementations in the context of an academic challenge, but also ability to take that knowledge and find interesting places to apply it in everyday situations.

Without further delay join me as I go over my favorite coding challenges of QHack 2022.

Games 100 - Tardigrade

Ah entangling living things! I remember when the Tardigrade paper came out December 2021 - I was excited when I saw that we would essentially be emulating the experiment through code. Little did I realize that this challenge would pose one of the biggest challenges to me. Being completely honest, many of the higher difficulty challenges, even within the Games category, were done before I finished this one. Why this one makes the list for interesting challenges was less in the solution itself, and more the eye opening process of how to apply the theory directly in code.

At its base, Games 100 requires us to prepare two states. The first being a maximally entangled Bell State, and the second introducing a third entangled qubit, representing the tardigrade. With the two states the goal is to calculate the level of entropy in the system, and see if introducing the tardigrade impacts the system.

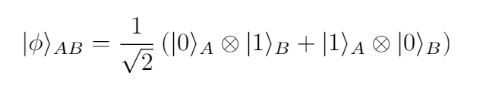

Bell State:

Tardigrade State:

In the template given to us for the challenge we first need to prepare the Bell state, calculate the entropy, and prepare the first part of our result, essentially the baseline. The Renyi entropy calculation function was provided, so this first part was trivial.

result = []

dev_n = qml.device("default.qubit", wires=2)

@qml.qnode(dev_n)

def circuit_no_t():

qml.Hadamard(wires=0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

return qml.density_matrix(wires=[1])

test1 = circuit_no_t()

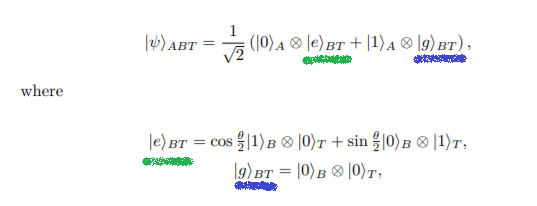

result.append(second_renyi_entropy(test1))For the tardigrade state we needed to add a few more steps. The initial theory I was working with was approaching it from preparing the Bell state between qubits AB and then introducing \(\left|e\right>_{BT}\) and \(\left|g\right>_{BT}\) to create the overall \(\left|\psi\right>_{ABT}\) state. While I was trying to do by gates, using illustrative tools like IBM's Q Explorer, I wasn't quite able to get it.

The "a-ha" moment was when I took a step back and went to basics if you will. Instead of trying to get the end state gate by gate, I realized I could calculate the required statevector by hand, then apply it to the three qubits to get \(\left|\psi\right>_{ABT}\) directly. This is why I say this particular challenge was important. Not for the end state of emulating a tardigrade (although I'll be honest it's a pretty cool thought experiment!), but more of a breakdown of _how_ the math works. From going to the initial equations and breaking it down to a point you can represent it in code with a one-liner - that is something that I will be able to take forward with me, in future, tardigrade-less problems.

$$ \begin{align*} \left| e \right>_{BT} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \cos{(\frac{\theta}{2})} \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \sin{(\frac{\theta}{2})}\\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$ $$ \begin{align*} = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ \cos{(\frac{\theta}{2})}\\ 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ \sin{(\frac{\theta}{2})}\\ 0\\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$ $$ \begin{align*} = \begin{bmatrix} 0\\ \sin{(\frac{\theta}{2})}\\ \cos{(\frac{\theta}{2})}\\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*} $$

Then:

\[\begin{align*} \left| g \right>_{BT} = \begin{bmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ 0\\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]Which allows us to get the final overall state we want:

\[\begin{align*} \left|\psi\right>_{ABT} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \bigl( \left| 0 \right>_A \otimes \left| e \right>_{BT} + \left| 1 \right>_A \otimes \left| g \right>_{BT}\bigr) \end{align*}\]Alright what a Math trip! So we have the final “state” we want to model, but how do we get that done? Ends up Pennylane has a simple way to accomplish that with QubitStateVector. We can take the statevector we manually went through and assign it directly.

@qml.qnode(dev)

def circuit_theta(theta):

## trying to set the statevector directly from formula

qml.QubitStateVector(np.array([ \\

0, \\

(1/np.sqrt(2))*np.sin(theta/2), \\

(1/np.sqrt(2))*np.cos(theta/2), \\

0, \\

(1/np.sqrt(2))*1, \\

0, \\

0, \\

0]), wires=range(3))

return qml.density_matrix(wires=[1])

test2 = circuit_theta(theta)

result.append(second_renyi_entropy(test2))This was the important part I took away from this challenge. While struggling with how to accomplish the same end result by a gate-by-gate basis, if you took a step back and understood what we were trying to accomplish, you can take that understanding and implement it directly.

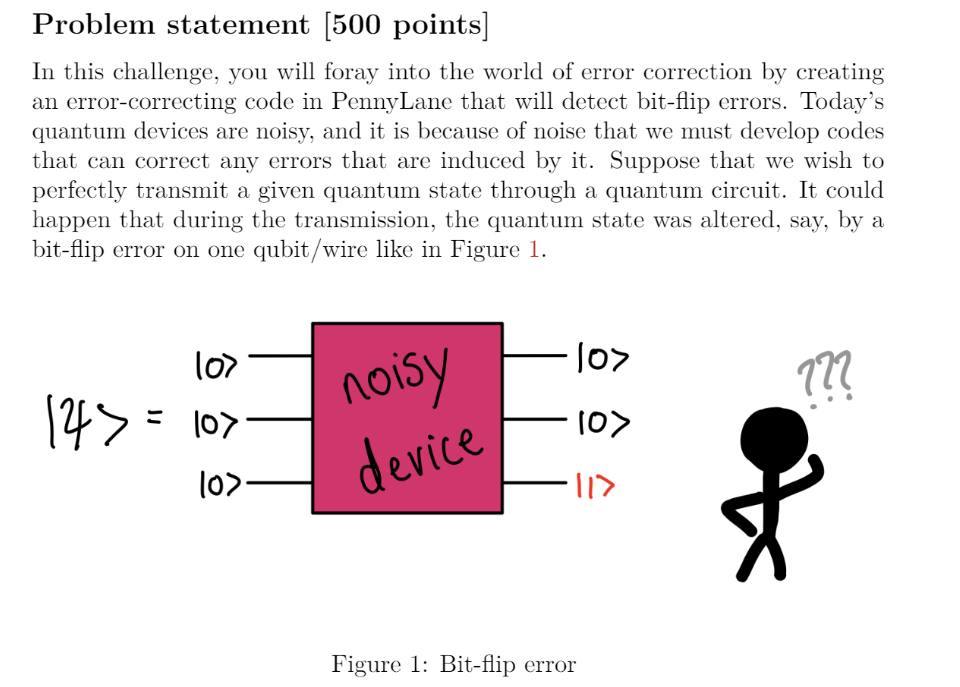

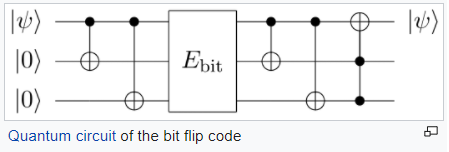

Pennylane101 500 - BitFlip Error Correction

Error correction! While this wasn’t the first time I’ve gone through implementing QEC, I feel this particular challenge helped explain more of the “why”. When starting out on this quantum journey I was happy with just implementing and seeing it work, but now I want to go a layer deeper and start understanding why something is working.

In this challenge we will be provided with two inputs - which qubit will have the error correction introduced, and at what probability. Our goal is to determine what the output probabilities for each qubit to have an error introduced, including the overall probability that no error is detected.

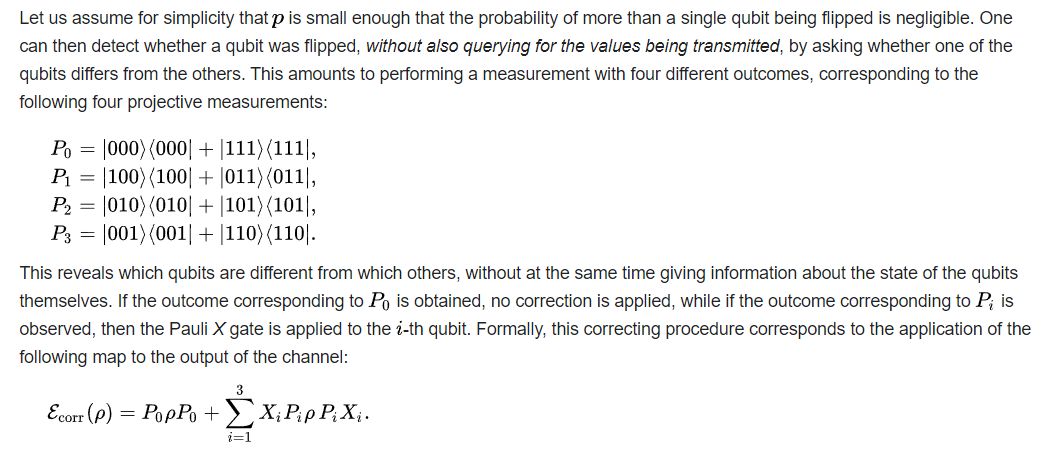

Reading more on the QEC theory we can boil down what we are trying to do with the following blurb:

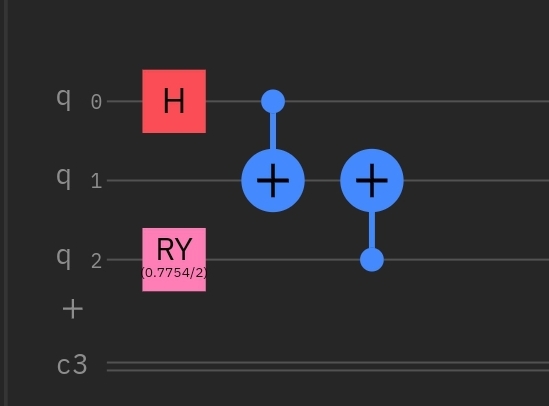

Which can be accomplished with the following circuit template.

Pennylane makes this implementation trivial with its BitFlip function, passing the probability, and which wire - both which are being supplied for us from the different input files.

qml.QubitDensityMatrix(density_matrix(alpha), wires=[0, 1, 2])

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 2])

qml.BitFlip(p, wires=int(tampered_wire))

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 2])

qml.Toffoli(wires=[2, 1, 0])All that is left at this point to is return the probability output of our two ancillary qubits. These values will represent out error proabilities.

return qml.probs(wires=[1,2])For the challenge, we need to return the probabilities in a specific format. That is simple enough to accomplish with the understanding of what values are represented in the circuit’s probability output.

result = []

result.append(circuit_output[0]) #probability of no error

result.append(circuit_output[3]) #probability of error on qubit 0

result.append(circuit_output[2]) #probability of error on qubit 1

result.append(circuit_output[1]) #probability of error on qubit 2And that’s it for the challenge. Based on the external resources above you can see how we could use this type of approach and apply a PauliX gate to the “errored” qubit. This type of action can prove invaluable in the NISQ era where we will be running into noisy infrastructure and learning how to apply QEC techniques.

Logic Challenges - Games 400/500

Both Games 400 and 500 are probably my favorite challenges of this year’s edition. Firstly because they were logic challenges - Quantum implementations of classic logical problems many of us have gone through before. These challenges allowed us to step through how to “Quantize” them from the classical world into our Quantum one. The second reason why I consider these challenges as my favorites are because they build into a core concept applicable in many algorithms and solutions we see out there - namely Phase Kickback. By solving Games 500 you really had to understand not only Phase Kickback works, but how you can use the interaction to glean useful information of our solution state in the context of a logic problem.

Games 400 - Find the Car

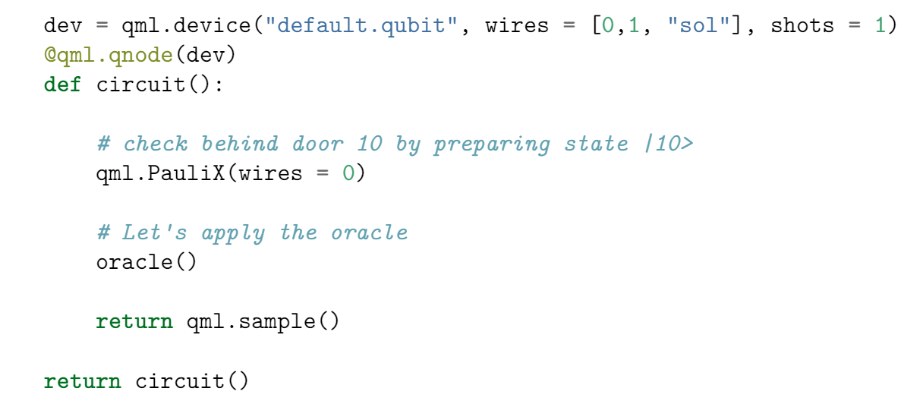

We started off with adapting the classic “pick a door” challenge with Games 400. The problem can be simplified down to we are presented 4 doors, behind one of them is a car, and our challenge is determine which door that is by leveraging an oracle (a fancy way of saying a function that will let us know if the right door is picked).

When the right door is selected, assuming above that the two qubits representing our the 4 door options is \(\left|01\right>\), the oracle PauliX flips and brings our input to \(\left|01\right>\), at which point the Toffoli gate would flip our third "sol" qubit representing we have found the car. It is trivial to see that any other combination of door selection would not result in the solution being triggered by the Toffoli gate.

Ok, we have the oracle setup here, so what’s the challenge? Herein lies the logical application. We have a one-to-one. If we run our circuit through the oracle and then measure, we have a definite answer on whether it was the right door or not. With 4 doors, that means we would need at most 3 measurements in a worst case scenario. The challenge is that we are restricted to making only 2 measurements. So in that worst case scenario where our first two choices are not correct, that still leaves a 50/50 between the remaining two doors. Ok, we can do better than that… can’t we?

What happens if we combine two checks together? We were told we could only measure twice, but what about doing multiple oracle checks before making the measurement? Would that provide us any additional information?

The following snippet shows how we would check for both 00 and 01 within the single measurement.

@qml.qnode(dev)

def circuit1():

# QHACK #

oracle()

qml.PauliX(1)

oracle()

# QHACK #

return qml.sample()So if the correct door is either 00 or 01, our solution would be flipped. This is potentially useful… but how? If we checked 00 and 01 in one measurement, then 10 and 11 on the second measurement we have narrowed the solution down to one of the two sets of doors, but we still don’t have a definitive answer. Ok let’s use this information and build on it. What if we overlay the measurements? Check 00 and 01, then 00 and 10? That seems like it would give us a concrete answer.

@qml.qnode(dev)

def circuit1():

# QHACK #

oracle()

qml.PauliX(1)

oracle()

# QHACK #

return qml.sample()

@qml.qnode(dev)

def circuit2():

# QHACK #

oracle()

qml.PauliX(0)

oracle()

# QHACK #

return qml.sample()

sol1 = circuit1()

sol2 = circuit2()

'''

So the two circuits check for

00 + 01 and 00 + 10

Then depending on the output it's 100% defined

If sols are 1/0 = 01 door

If sols are 0/1 = 10 door

If sols are 1/1 = 00 door

If sols are 0/0 = 11 door

'''

# process sol1 and sol2 to determine which door the car is behind.

sol11 = sol1[2]

sol21 = sol2[2]

if sol11 == 0 and sol21 == 0:

return 3

if sol11 == 1 and sol21 == 1:

return 0

if sol11 == 1 and sol21 == 0:

return 1

if sol11 == 0 and sol21 == 1:

return 2And there we go, Games 400 completed. This was a good first step to adapting a classical problem to a quantum circuit, but as we shall see in Games 500, we can take this even further!

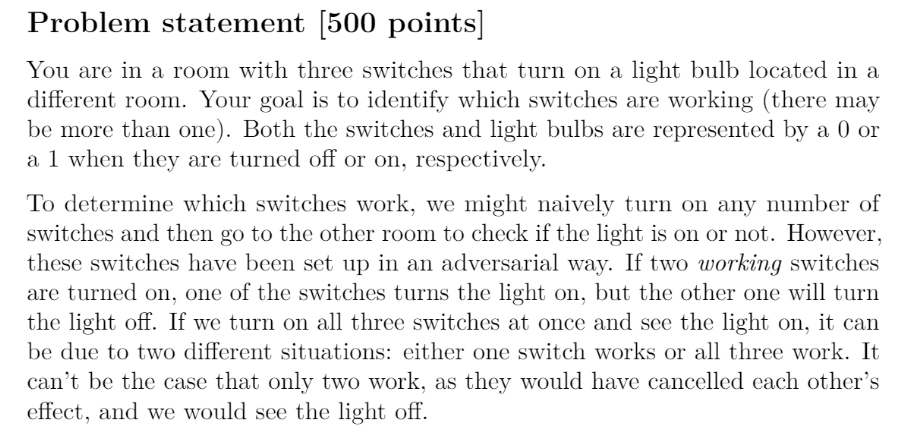

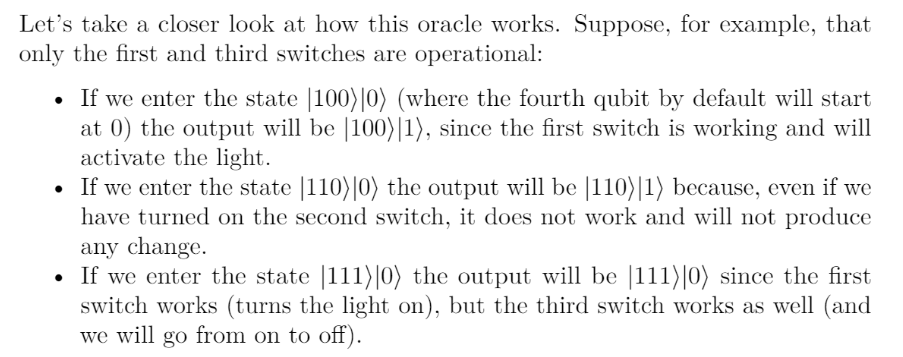

Games 500 - Switches

Let’s do another classic - the light switch logic problem. There have been many flavors over the years, and this one is no different. The main difference is that the switches here are acting in an adversarial approach - specifically if two individual switches would turn on the bulb, if both are toggled the light will turn off. This will need to be taken into consideration as we approach the solution.

We can start the solution by approaching this the same way we did Games 400 - adopting the problem statement into a quantum model. Since our solution needs to be flexible enough to work with different sets of switches that “turn on” the bulb we can model it as an oracle.

Ok this sets our stage. Now to start thinking about how to implement it. Since we can only do a single measurement we wouldn’t be able to follow the same overlapping solution we used in Games 400. My thinking going into it was that we needed to be able to gather information on a single switch basis. If we were to use a few ancillary qubits this becomes trivial, store the results per switch into the ancillary qubits, however we are working with a strict 3 switch and 1 bulb model.

This is where the Quantum concept of Phase Kick-Back comes in. The documentation is worth reading in its entirety but the condensed version is that by moving away from the Z-basis (computational basis) to the X-basis using Hadamards we can “transfer” back information from our lightbulb when it is turned on. In short, I will use the switch qubit itself to store whether it turns on the lightbulb.

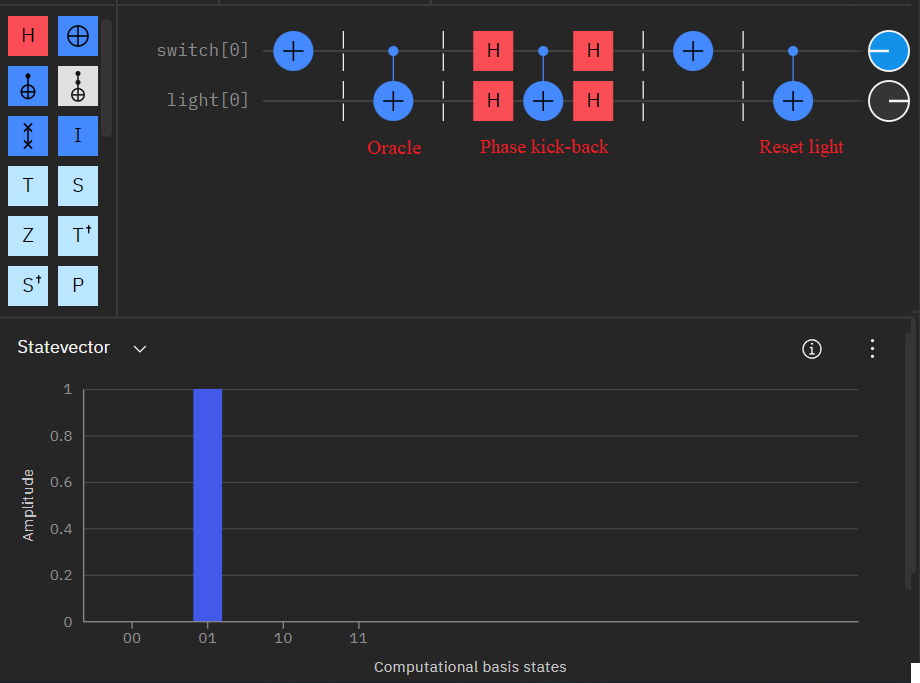

To give an example of how we can leverage phase kick-back let’s look below at a simplified example with 1 switch and bulb. The oracle in this case is just a CNOT to illustrate the concept but can work with any complex oracle that allows the switch to turn on the bulb.

If you follow the circuit you will notice that when the switch doesn't doesn't turn on the light we finish off with \(\left|00\right>\). If the switch does trigger the oracle however... then while we end up resetting the light bulb, the switch itself remains "on", giving us an indication that the state was kicked back from the turned on bulb.

With this we can then expand the process for multiple switches and come up with a suitable approach.

qml.PauliX(0)

oracle()

qml.Hadamard(0)

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.CNOT(wires=[0,"light"])

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.Hadamard(0)

qml.PauliX(0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[0,'light'])

qml.PauliX(0)

qml.PauliX(1)

oracle()

qml.Hadamard(1)

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.CNOT(wires=[1,"light"])

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.Hadamard(1)

qml.PauliX(1)

qml.PauliX(0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[1,'light'])

qml.PauliX(0)

qml.PauliX(1)

qml.PauliX(2)

oracle()

qml.Hadamard(2)

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.CNOT(wires=[2,"light"])

qml.Hadamard("light")

qml.Hadamard(2)

qml.PauliX(2)

qml.PauliX(1)

qml.PauliX(0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[2,'light'])

return qml.sample(wires=range(3))We need to pauliX the subsequent switches and at first it may not seem intuitive. If the previous switch does not trigger the light, then turning it “on” would not impact the overall check for the next switches. If however the lower switches do trigger the light, we need to temporarily turn them “off” to check the subsequent switches. By cascading the checks in this way we are testing each switch individually and ensuring the kick-back sample measurements provide us the correct solution.

I really enjoyed this challenge as it does not only cover an important quantum computing concept, but goes a step further and allows us to explore how we can leverage it practically. Phase kick-back is an important concept in itself, but also becomes an important part of more complex algorithms like Grovers.

Reflective Summary

With that we reach the end of the coding challenge coverage. I am happy to have participated, however with the event lasting almost two weeks I’m also happy to take a break now that it’s over. While the challenges themselves were awesome I did have a few comments on the event structure itself.

The Challenge Portal

Having a single login for each team is… frustrating. Coming from a decade of working in Identity and Access Management, sharing credentials for a single team grinds my gears. I would love to see a CTFd style implementation for individual sign up and team structure.

Community Discussions

While struggling against the challenges is literally part of the process, I felt there was a miss on the learning angle throughout the event. This felt more like a pure competition than an event focused on getting participants to learn. If that was the ultimate goal by the organizers, great, however I feel the approach to team discussion was a bit too harsh. By restricting the cross talk in slack the team did avoid spoilers or solutions from being shared. I completely agree with keeping the event clean from that perspective. However considering the amount of teams and individuals involved from around the world, I was shocked at how little the community was chatting.

In the last two years I’ve participated in many different events in Quantum while I have also been involved in the CyberSecurity CTF world for many years. In short, I love participating in gamified learning events. What I can say is that building that community, having those conversations, and fostering those people connections were arguably as important, if not more important, than the knowledge gained in the event itself. I feel that QHack this year was very focused on a “sanitized” environment, which did steer individuals to self-learning, in itself a good thing, but considering the global nature of the participants I would have loved to see more interaction on the coding challenges similar to what I saw in the twitch sessions.

Event Length

I’m torn on this last point. While I appreciate the two weeks to work on challenges on my own time, the two weeks were basically living and breathing QHack only. I would love to see potentially a more condense event in the future, maybe a week, where people could buckle down without feeling burnt out by the end.

With all this said - I highly suggest this amazing event. To anyone thinking about participating in these types of Quantum hackathons I simply say “take the plunge”. Regardless of your background, there is something to learn and you will come out of it knowing more than you did going in.

Here’s to QHack 2023. I’m looking forward the next iteration already!

Thanks folks, until next time!